The History of Gongbi Painting

Julie M. Segraves

Regarded as China’s most conservative and time-consuming brush technique, the fine line or gongbi method of painting combines fine black lines with multiple layers of both ink-shading and unmixed transparent and opaque colors.

Historically, the gongbi method has been used to depict figure, bird and flower subjects. During the Tang dynasty (618–907), fine line painting flourished, with well-known artists like Zhang Xuan (713–755) and Zhou Fang (750–800) depicting the splendors of court life.

By the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), gongbi was used extensively to illustrate birds and flowers as well. But by the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), the Chinese literati began to exhibit a preference for xieyi, believing that this more spontaneous brush method was better suited to communicating the artist’s inner feelings, and the realism of the gongbi method fell out of favor among many artists.

Although well-known Ming dynasty (1368–1644) artists like Tang Yin (1470-1523) and Qiu Ying (1494–1552) continued to include gongbi in their painting repertoire, it was not until the 18th century that the gongbi method received a renewal of interest and attention, sparked by the arrival of Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766), a Jesuit missionary.

Castiglione had been charged with the task of creating a synthesis of European methods and traditional Chinese media and formats at the Imperial Painting Academy. Chinese gongbi court painters were soon perfecting a fusion of painting techniques, combining the linear perspective of Western-style realism with traditional Chinese brushwork. Other excellent Qing dynasty (1644–1911) artists continued to use the gongbi techniques including Yuan Shouping (1633–1690) and Ren Xiong (1823–1857).

However, with the fall of the Qing dynasty and the demise of the traditional patronage system and the Imperial Painting Academy, many Chinese gongbi and xieyi artists were forced to pursue new avenues of income and modernize their painting techniques. Some artists looked to Japan and the West for new inspiration and income. Other artists living in Shanghai turned to commerce, combining their gongbi skills with Western techniques to create commercial pieces for the popular calendar prints, Yuefenpai.

With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, and the government’s fondness of Socialist Realistic oil painting, the popularity of the gongbi technique declined even further.

After the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), artists began exploring a host of Western art and media, especially the techniques and principles, believing that the practice of gongbi painting was simply too old fashioned and too demanding, and that the gongbi genre needed to be relegated to China’s past.

Yet, in the early1990s, a new generation of young, traditionally trained ink artists emerged to revitalize the gongbi tradition by mixing the centuries-old techniques with their own. These new gongbi paintings reflect the artists’ personal concerns, as well as the changing Chinese society in which they live, making the work by the three exhibit artists all the more surprising and compelling.

Zhu Wei

The son of a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) doctor, Zhu Wei was born in Beijing on the eve of the Cultural Revolution. His parents hoped that he too would enter the medical profession. However, Zhu had other ideas, and he enlisted in the PLA at the age of sixteen. He then began a course of study at the Art College of the PLA, where he excelled in creating propaganda art and posters. After graduating in 1989, Zhu attended the China Painting

Academy and the Beijing Film Academy, where he graduated in 1993. Despite his disparate academic art training, Zhu has remained a diligent student of traditional Chinese art, especially the challenging technique of gongbi painting for which he is acclaimed.

The early 1990s was a particularly volatile time for artists in China. Like many of his colleagues, Zhu chose not to be affiliated with any government institution or art academy. While many of his fellow artists did turn to oil painting or acrylic on canvas, the preferred media of the Western art market, Zhu chose to develop his signature gongbi painting style, reshaping, transforming and transcending this centuries old painting technique by employing both classical and ingenious new painting fundamentals to achieve his artistic statements on China’s society and politics. With his formable painting skills, Zhu has the unique ability to create work that initially appears deceptively simple, even whimsical, yet many of his more than 1000 paintings are, in fact, powerful political portraits of PLA soldiers, Party cadres and ordinary citizens, and their life in China today

China Diary No. 19, ink and color on paper, 103 x 88 cm

One of Zhu’s earliest gongbi paintings featured in the exhibit is China Diary Number 19, created in 1998. Initially Zhu has selected a heavy sheet of Xuan painting paper, creating interesting hollows and indentations, before painting the paper ground with a flaxen color. The work features a reclining party official lost in slumber on a comfortable pillow and covered by a blanket to guard against drafts. The party bureaucrat has all of the physical attributes typically found in Zhu’s painted political parodies: large head, hands, feet, and nose, but closed unseeing eyes and small unhearing ears. Zhu believes that most party CCP representatives glean little practical information from these gatherings and that many attendees simply sleep their way through the wearisome assemblies. Although Zhu’s depiction of this political cadre is satirical, it also appears to be accurate, illustrating a passive party person who has few dreams of how to make the past serve the present in contemporary China.

Vernal Equinox No.11, 2007, ink and color on paper, 160 x 120 cm

Spring Equinox Number 11 was painted in 2007 and illustrates one of Zhu’s contemporary China social landscapes. Zhu has painted a yellow-colored surface with six floating egg-shaped figures seemingly not tethered to the ground, similar to Western roly-poly toys that tend to right themselves when pushed over. Indeed, some Chinese folk artists craft similar hollow clay shapes to resemble plump, dimwitted bureaucrats, thereby mocking the officials’ incompetence and ineffectiveness.

Zhu’s six figures all appear to be isolated in their spring outings and all are featured with miniature feet turned inward with hands shoved into their padded jacket pockets. Sporting wind-swept hair, all figures seem to lack actual personalities. Several have indistinct facial features, while the remaining figures’ faces register dejection or indifference. Indeed, Zhu’s weathered and distressed paper surface figure details are achieved by the artist through repeated immersions into water and subsequent crunching of his strong, Xuan paper. The painted people are flanked on both sides by several of the artist’s seals in clerical script, with one featuring “www” but missing the actual Internet address. Peach blossoms punctuate the left painting side and a peach with leaves is featured on the right painting side, both considered symbols not only for spring and immortality, but also for love and romance. Still, passion seems elusive for the figures featured in this work, and all their dreams and desires for love and affection appear to have gone unanswered.

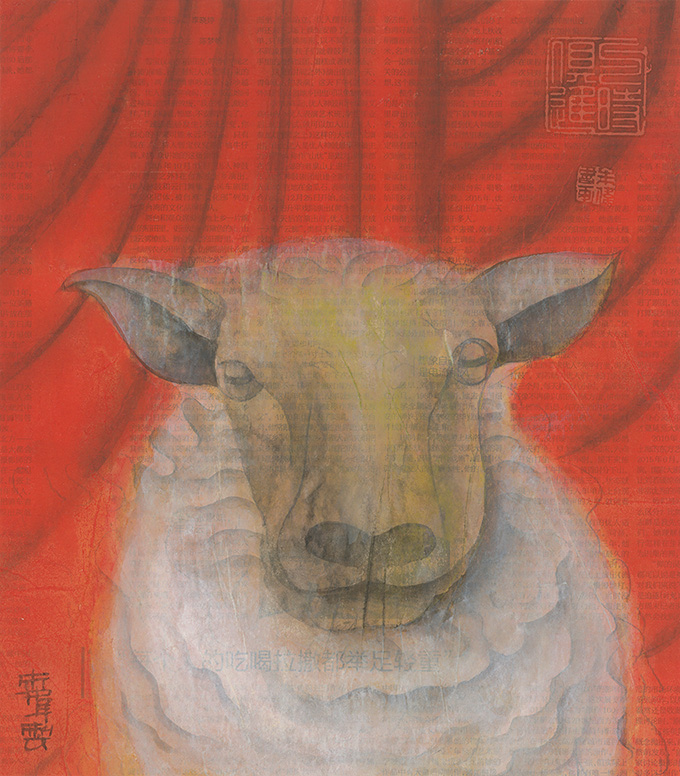

Zhu has repeatedly used overlapping red curtains as a persistent art element for many of his Ink and Wash Research Lecture Series paintings, presenting his viewers not only with a painted abstract backdrop, but one that is also red, a color full of symbolism in traditional and contemporary China, synonymous with both happiness and the communist ideology. In one painting the red curtains offer a background for Zhu’s own political caricature for the average Chinese citizen, a sheep - a tamed animal famous for being timid, easily led, and stupid. Zhu’s somber sheep peers piercingly through the artist’s black painted haze, which further hinders both the animal’s eyesight and insight.

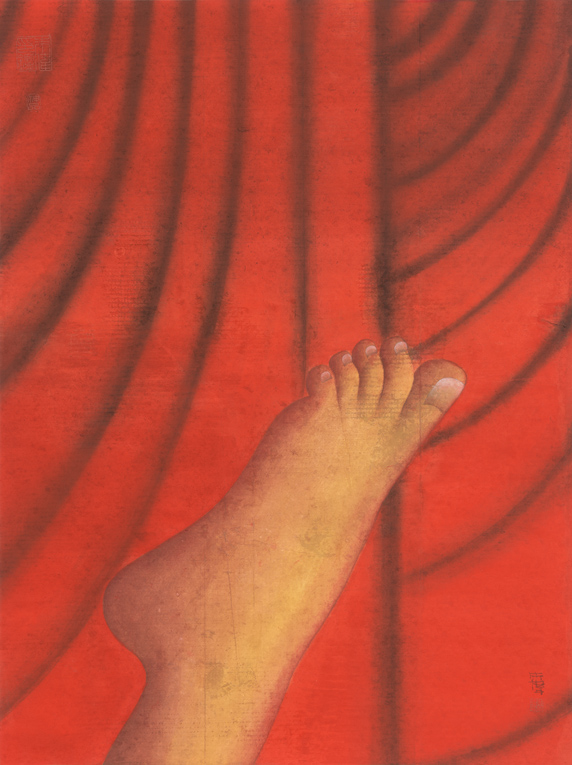

Ink and Wash Research Lectures series No.8, 2014, ink and color on newspaper, 84 x 61 cm

Another Ink and Wash Research Lectures Series painting focuses on an unlikely subject - a foot- against the red curtained backdrop. It is not known if Zhu actually drew upon the art of Andy Warhol, the leading figure in Western Pop Art, for his theme. Warhol recruited friends, lovers, collectors, and celebrities alike, using their feet as a major subject in his own whimsical art, which was tied to his personal quest of exposing the triviality of the United States’ consumer culture. But unlike Warhol, it is not apparent if Zhu’s single painted foot is simply just a foot, or if it represents the artist’s personal statement on contemporary China’s pursuit of its own burgeoning consumer culture.

Ink and Wash Research Lectures series, 2018, ink and color on paper, 67 x 80 cm

In two recent Ink and Wash Research Lectures paintings Zhu features one simple, red, hanging curtain and he has joined this art element with two unassuming images. In one work, a white scarf is draped on the left red curtain side. White scarves have special meaning in various cultures. In China, female opera figures use them when performing, and in Tibet white scarves are presented as gifts and used for special offerings. In traditional China the white color was viewed both as a sign of purity and also as a symbol for death. But in this painting, the color white and the scarf itself are purely art elements, without any elusive connotation. Indeed, the artist is simply playing with forms, art elements, and the materials that he has used on his painting surface. In the other Ink and Wash Research Lectures painting, an indistinct, abstract form is featured on the left red curtain side. Zhu has painted over both images with a murky black wash, obscuring the art elements and creating a feeling of mystery and unease.

Ink and Wash Research Lectures series No.19, 2016, ink and color on newspaper, 32 x 28 cm

In the final Ink and Wash Research Lecture Series exhibit painting, Zhu explores the relationship between history and contemporary culture by creating a political parody of a sheep, who like a Chinese citizen, is typically meek and easily led. Zhu has exchanged his distinctive and exclusive Xuan paper for common, unexceptional newsprint as his painting surface, perhaps hinting that the government’s control over everyday media alters its citizen’s perception of daily news and life in contemporary China.

This is one of twelve newsprint paintings in the series, and all reveal a blurred image of a central figure with indistinct features in front of a red curtain backdrop. On this painting, the artist has applied layers of mustard-color pigments cover both figure and flag, obscuring the details of both. The artist then further distresses the painting surface, distorting the actual images of both art elements while making his statement on the Communist party’s unrealistic socialist society.